A blog post this week in three parts. A folktale. A framework from this week's Torah portion. And an apology.

The folktale*: There was a very wealthy man who loved only two things in life: work and cake. When he wasn't working he was admiring or eating cake. He had a favorite bakery that sold the most beautiful and delicious cakes. He went there every day on his way to work.

Once when he was walking out of the bakery with a beautiful slice of cake, the man stumbled. His cake fell to the ground. His piece of cake rolled in the dirt where it was covered with pebbles and grass. On his way back into the bakery to buy a replacement piece of cake, the man noticed a homeless person peering into the bakery's window. The man picked up the dirty piece of cake, handed it to the homeless person, and went inside to buy more for himself.

That night as the man drifted off to sleep, he dreamt of rising to heaven. In his dream, the whole of heaven was one giant bakery. The tables were filled with people enjoying beautiful and delicious looking cakes. He ordered a slice of cake from the menu. He waited. A long time.

Finally, the server brought him a piece of cake. But instead of the slice he had selected, the cake on the plate in front of him was covered with pebbles and grass. "That's not the cake I ordered!" the man objected to his server.

"I'm sorry sir," the server explained, "but in this bakery, you can order only from what you've sent ahead through your treatment of others. We looked everywhere, but the cake in front of you was the only cake in the back with your name on it. It's the only thing you sent ahead."

With that, the man awoke from his dream. He was glad to have more time to change his ways enabling him to "send ahead" more positive ways of treating others.

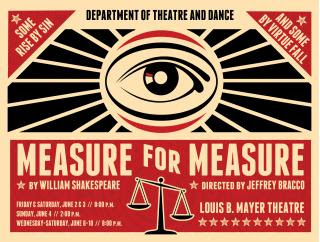

The framework: That story came to mind this week because the Torah portion, Ki Tavo (lit. "when you enter") seems to echo the theme of "measure for measure" -- that we are treated according to how we treat others.

The Torah portion includes a list of blessings and curses. Blessings that come to those who follow Torah when entering the land of Israel. And curses that come to those who don't follow Torah. It is a familiar motif: blessings and curses. But there is something unique about this particular set.

Unlike other Torah lists of blessings and curses, this set seems to align the blessings and curses, as if match them up with each other. For example, being blessed in one's comings and goings if one follows Torah is aligned with being cursed in one's comings and goings if one does not. (Deut. 28:6, 19). Those who follow Torah will be blessed to see their enemies retreating and scattered on seven roads, while those who do not follow Torah will be cursed to find themselves retreating and scattered on seven roads. (Deut. 28:7, 25).

A kind of measure for measure framework. And it comes every year in Torah just ahead of the Jewish new year, the season when we reflect on our conduct during the year about to end in order to set our intentions and elevate our conduct in the year about to begin.

As we approach the Jewish season of reflection, repentance, and renewal, Torah seems to be reminding us that our blessings and curses are carefully weighed -- measure for measure based on our conduct.

Similarly, the rabbis teach, "the same standards that we use to deal with others are the standards that are applied to us.” (Sotah 8b) In other words, if we are kind and compassionate, we can expect to be judged with kindness and compassion. If we are unfair, unduly critical, or unforgiving with others, we can expect that others will treat us the same way. As we judge others, so, too, will we be judged.

That night as the man drifted off to sleep, he dreamt of rising to heaven. In his dream, the whole of heaven was one giant bakery. The tables were filled with people enjoying beautiful and delicious looking cakes. He ordered a slice of cake from the menu. He waited. A long time.

Finally, the server brought him a piece of cake. But instead of the slice he had selected, the cake on the plate in front of him was covered with pebbles and grass. "That's not the cake I ordered!" the man objected to his server.

"I'm sorry sir," the server explained, "but in this bakery, you can order only from what you've sent ahead through your treatment of others. We looked everywhere, but the cake in front of you was the only cake in the back with your name on it. It's the only thing you sent ahead."

With that, the man awoke from his dream. He was glad to have more time to change his ways enabling him to "send ahead" more positive ways of treating others.

The framework: That story came to mind this week because the Torah portion, Ki Tavo (lit. "when you enter") seems to echo the theme of "measure for measure" -- that we are treated according to how we treat others.

The Torah portion includes a list of blessings and curses. Blessings that come to those who follow Torah when entering the land of Israel. And curses that come to those who don't follow Torah. It is a familiar motif: blessings and curses. But there is something unique about this particular set.

Unlike other Torah lists of blessings and curses, this set seems to align the blessings and curses, as if match them up with each other. For example, being blessed in one's comings and goings if one follows Torah is aligned with being cursed in one's comings and goings if one does not. (Deut. 28:6, 19). Those who follow Torah will be blessed to see their enemies retreating and scattered on seven roads, while those who do not follow Torah will be cursed to find themselves retreating and scattered on seven roads. (Deut. 28:7, 25).

A kind of measure for measure framework. And it comes every year in Torah just ahead of the Jewish new year, the season when we reflect on our conduct during the year about to end in order to set our intentions and elevate our conduct in the year about to begin.

As we approach the Jewish season of reflection, repentance, and renewal, Torah seems to be reminding us that our blessings and curses are carefully weighed -- measure for measure based on our conduct.

Similarly, the rabbis teach, "the same standards that we use to deal with others are the standards that are applied to us.” (Sotah 8b) In other words, if we are kind and compassionate, we can expect to be judged with kindness and compassion. If we are unfair, unduly critical, or unforgiving with others, we can expect that others will treat us the same way. As we judge others, so, too, will we be judged.

The Yom Kippur prayers include a phrase from Torah, "salachti keed'varecha," – I forgive as you say,” It is a liturgical affirmation that God forgives us. In its Torah context, it is God saying God will forgive the people Israel just as Moses has asked. But another way of reading it is, “I will forgive you, as you forgive others.”

Measure for measure: As judge others, so we will be judged. As we forgive others, so will we be forgiven.

Measure for measure: As judge others, so we will be judged. As we forgive others, so will we be forgiven.

The apologies: Which brings me to two apologies I offered to the school community for things I said recently while speaking to the whole community. The first involved a quick laugh I got by making fun of a geography mistake on a slide show about where students spent their summer. I did it for the cheap laugh. I apologized publicly to the student who made the slide show and to all those who might have been intimidated by my poking fun at a student's mistake. That is not the environment I want to create at school. I needed to apologize, try to compensate for my harm, understand my motivations to act as I did, and commit to keeping myself from doing something similar in the future. That is what I tried to model with my apology in front of the whole school community.

I offered a similar apology for a socially provocative joke of Sarah Silverman's that I read to the school community. I apologized not because it was provocative, but because the joke pitted one group against another in ethnic identity terms. The joke was poignant and powerful, which is why I shared it. But it also was stigmatizing, a fact to which my own ethnic privilege blinded me. I needed to apologize to the community for having caused offense on account of my insensitivity. compensate for my harm, model the need to apologize even if (especially if it is not easy), and commit to keeping myself from doing something similar.

I hope I accomplished that in front of the students this week by taking responsibility for my behavior. As I told them, I apologized publicly in the same manner in which I caused the hurt; I looked deeply at what prompted my behavior and explained it by way of modeling and so that I could sincerely commit myself to avoid repeating it. Then I invited all our students and educators to follow my lead. to seek forgiveness.

I encouraged them to remember that seeking forgiveness does not necessarily feel good, at least initially. It can stir up old hurts or resentments or even old shames, which is why we tend to avoid it. Seeking forgiveness and granting it each take courage, generosity, and hope. Courage to initiate a process, not a one-time event. Generosity to accept both honest feedback and sincere apologies. And hope that we will be forgiven to the extent that we forgive others.

(*My presentation of this folktale is adapted from the version appearing in Peninnah Schram's Chosen Tales (1995) p.357)

I offered a similar apology for a socially provocative joke of Sarah Silverman's that I read to the school community. I apologized not because it was provocative, but because the joke pitted one group against another in ethnic identity terms. The joke was poignant and powerful, which is why I shared it. But it also was stigmatizing, a fact to which my own ethnic privilege blinded me. I needed to apologize to the community for having caused offense on account of my insensitivity. compensate for my harm, model the need to apologize even if (especially if it is not easy), and commit to keeping myself from doing something similar.

I hope I accomplished that in front of the students this week by taking responsibility for my behavior. As I told them, I apologized publicly in the same manner in which I caused the hurt; I looked deeply at what prompted my behavior and explained it by way of modeling and so that I could sincerely commit myself to avoid repeating it. Then I invited all our students and educators to follow my lead. to seek forgiveness.

I encouraged them to remember that seeking forgiveness does not necessarily feel good, at least initially. It can stir up old hurts or resentments or even old shames, which is why we tend to avoid it. Seeking forgiveness and granting it each take courage, generosity, and hope. Courage to initiate a process, not a one-time event. Generosity to accept both honest feedback and sincere apologies. And hope that we will be forgiven to the extent that we forgive others.

(*My presentation of this folktale is adapted from the version appearing in Peninnah Schram's Chosen Tales (1995) p.357)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment Here